Five-year-old Fang Jiawei's parents were extremely worried about their son's future. They believed that if he couldn't enroll in a standard school, he would not find a job or support himself after they passed away. "They had even decided on a drastic plan - a family suicide," says Alexander Haase. The German filmmaker worked with British documentary-maker Robin Aspey to shoot a film about the families of autistic children at the Beijing Stars and Rain School in Beijing's northern suburbs from last August to October. Founded in 1993 by Tian Huiping, a mother of an autistic boy, the school is a grassroots educational institute providing special education for families of autistic children. It conducts an 11-week, tailored course for both children and parents. The school has helped more than 1,000 families of autistic children across the country and has won support from an army of volunteers from around the world. In the face of such desperation, Fang's parents were eager to enroll in the school's program. Stars and Rain bases its training on theories of Applied Behavior Analysis (ABA). This method teaches parents how to continue their and their children's educations after completing the program. "The parent holds something the child likes and guides him to come up and say the word 'yao' (I want it). It is a simple game, even for a 2-year-old," Haase says. But when the parents tried to get Fang's attention with fruits, sweets and toys, the boy just ran back and forth across the classroom. "They look like ordinary kids upon first sight. Soon, you will find they are always alone; they don't speak to or play with each other - or even with their parents," Haase says. "Medically, they are called autistic children. But I prefer another warmer term- 'children of the stars', which is also the title of our film." Autism is a developmental disability that causes problems in communication and social interaction. Haase had only a limited knowledge of autism before he became the film's producer. He first heard the word in the widely acclaimed film Rain Man. He was impressed most by the lead character's savant-like capabilities of calculation. "It is a pity that autistic people have long been left in the shadows and isolated from mainstream society," says Haase, a business administrator who has lived in Beijing for about five years.

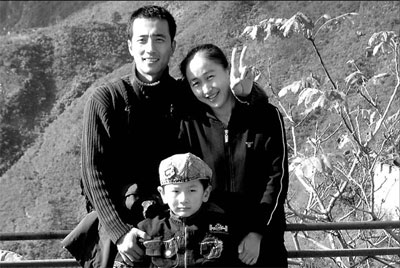

About a year ago, he met Aspey, a Londoner who had a friend with autistic children. Aspey had traveled throughout Europe, North America and Southeast Asia before finally deciding to shoot his film in China, and Haase joined the team. Their close observations have bettered the team's understanding of the difficulties faced by families with autistic children. They say they hope that the film's screening would raise awareness about these families. Aspey remembers that when they first entered the school with cameras, the parents were both curious and skeptical. Some were alarmed and asked what they were doing. Their Chinese assistant Dai Yuerong explained that they would stay to shoot a documentary about autism, which alleviated their concerns. Tian told them that the school had moved four times because of some neighbors' hostilities. Many local residents thought these "odd" children were "insane and dangerous", says Tian, who is on a short stay in Germany learning more about autism treatment. The school had 75 children between age 4 and 5 divided into five classes. Fang Jiawei caught the team's attention while they were tracking the children's progress. "The boy was typical; he couldn't speak or recognize his parents. He made no eye contact with others. And he knew nothing about the dangers around him," Haase says, recalling his first impression of the boy. "He was in unstable moods and was often aggressive towards his mother." Fang's parents, who came from Northeast China, hoped the documentary would alert other people to the realities of autism. Despite their desperation, "they are asking for social help with great dignity", Aspey says. Each child at the school is assigned several tasks of graduated difficulty levels. Before moving on to the next task, they must complete the previous level's task and also pass their weekly exams. Fang Jiawei's first class assignment was to complete a puzzle - an easy assignment for most 5-year-olds - designed to help the child learn concentration, which is vital to improvement. But Fang didn't respond to his parents' or teachers' instructions. When his mother tried to stop him from running away, he bit and punched her. "He wanted to express that he couldn't do it," Haase says. "The parents didn't cave in and kept bringing him back to the puzzle in vain. They went on to practice it after school. Every day was a tiring cycle of countless repetitions, failures and disappointments for those autistic families. "Sometimes I said to myself: 'Well, that's enough; I can't stand it anymore'. "We wanted to drop the camera and leave. The parents seemed to be on the edge of mental collapse. "But the strong power of love and patience pulled them back, and so it did to us," he says. Such desperation dominated the lives of other families at the Stars and Rain. Four-year-old Zhang Xi's reward for practicing her assignment was her mother's big hugs. Unlike many other parents who consistently came as couples to accompany their children during the course, Zhang Xi's father only showed up for his daughter's first day. Since then, he spent most of his time in Internet cafes. The families of autistic children could legally have another child, but Zhang's mother feared her girl would be abandoned if she had a younger sister or brother. Despite dealing with so many depressing moments, Haase and Aspey wanted to add some brightness to the film. So, they included segments such as the Fang family's trips to the Great Wall and Chaoyang Park. The boy behaved like any other child, and the family had a rare day of joyfulness. By the end of the program, Fang had learned 30 simple words. He also achieved a vital breakthrough - one day, he looked into his mother's eyes and recognized her. The parents burst into tears. Such a simple moment could bring great hope to other families, Aspey believes. "We were happy for them, although we felt a little bit regretful that Fang still doesn't recognize us, as we were with him for three months," he says. They say they were most moved by these parents' selfless love for their children. Fang's father worked in the IT industry and planned to run his own company before his son was diagnosed with autism. And his mother had dreamt of a career in the fashion business. But they gave up their career pursuits to devote all of their energy to treating their son's disease, which would take decades. The documentary is currently in its final cut under the sponsorship of the German Association of Autism and is scheduled for completion this month. "We don't want the audience to just feel sad about those families," Hasse says. "The three-month training is just a small battle those families have won over autism. They will return home to fight with the old feeling of sorrow and overcome future difficulties without professional assistance." The filmmakers say they hoped a platform could be created that would allow autistic families to receive the lifelong financial and scientific support their children need. (China Daily 06/27/2007 page20) http://www.chinadaily.com.cn /cndy/2007-06/27/content_903252.htm http://www.globalhealthmagazine.com/dim_sum/dim_sum/ http://www.de-cn.net/mag/flm/de5155769.htm

| website design by www.chenard.cn. All Rights Reserved 2007

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||